Hooking the Reader

One of the many reasons I love having writer friends is because they write posts like this that inspire me to get back to work revising my novels.

I met Ann at a writing workshop on Martha’s Vinyard. We wrote, shopped and made delicious pizzas. Three years later our small group still keeps in touch, cheering each other on and offering encouraging words when the writing life gets difficult.

Workshops and retreats are not only places to grow as a writer they’re also fertile ground to grow lasting friendships.

I’m excited to share this post on hooking the reader.

Introducing Ann Finkelstein!

Hooking the Reader

Thank you, Krista, for asking to me write a guest post on your blog.

I serve as Mentorship Coordinator for the Society of Children’s Book Writers and Illustrators in Michigan (SCBWI-MI). This year, we held two mentorships for novelists. In an effort to improve my own writing, I read all of the submissions carefully and studied the judges’ comments. I’m happy to announce that I learned something important.

The judging for this competition is anonymous, so unfortunately, I can’t include the name of the super-smart woman who inspired this post. In this judge’s comments, the idea of raising the stakes was a recurrent theme. The anonymous judge can be paraphrased as: If the protagonist can walk away from the problem, the reader can walk away from the book. In other words, the problem has to be so important to the protagonist, that neither quitting nor failing is an option.

I considered some of my favorite novels and how their authors raised the stakes. First, I realized that the character’s challenge has to be personal. His or her history and personality impact the severity of the problem. Second, the problem may not be an issue to the reader, but a skilled writer will convince the reader to accept the situation.

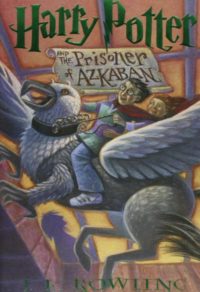

In Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban by J.K. Rowling (Scholastic, 1997), Harry wants to visit the village of Hogsmead even though escaped murderer, Sirius Black, is supposed to be hunting him. Probably, every reader of this series would love to visit Honeydukes, The Three Broomsticks and Zonko’s Joke Shop. Of course, Harry wants to leave school and have fun with his friends. Of course, he doesn’t want to be left behind with the little kids. But why is going to Hogsmead so important to Harry that he ignores the warnings about Sirius Black? Harry risks his life to go on a daytrip because the wizarding world is the only place Harry has ever belonged. He was excluded from his true home and community for most of his life. Being left out again is unbearable. The reader understands Harry’s need to belong and why he must go to Hogsmead.

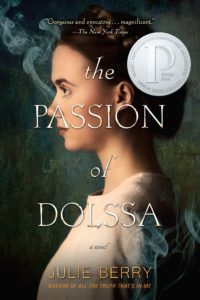

Julie Berry’s The Passion of Dolssa (Viking, 2016) involves a problem that at the outset might be harder for readers to understand. Dolssa lives in France in 1241 during the Inquisition, a dangerous time for anyone whose religious views deviate even slightly from Church doctrine. Dolssa believes that Jesus is her beloved and that her role is to spread Jesus’ teachings. A modern reader might easily take Dolssa’s mother’s view: don’t tell the inquisitors what you really think, join a convent or marry a nobleman, do whatever is necessary to survive. However, Dolssa’s faith is greater than any of these practicalities. At her interrogation by the inquisitors she says, “I can no more retract or deny what I have said about my beloved than I could choose to stop breathing. Against my will, breath would flow into my lungs; against your will, speech will flow from them also.” The reader is swept up by Dolssa’s passion.

To conclude, the recipe for increasing the stakes is simple.

- Determine the Most Important Thing in your main character’s life.

- Convince the reader that your protagonist is credible.

- Take the Most Important Thing away from the protagonist.

- Write a novel about how the protagonist tries to recover the Most Important Thing.

Easier said than done.